Personalities & Performance

Are you and your job the same color?

By Patricia Kitchen, Change@work

Understanding your work style, counselors say, can help you find the right occupation.

It was 10 years ago that Debbie Cutler came to a career crossroads: Should she continue in her accountant role with one of the big firms? Or was it time to move to a different company — or a different line of work?

She had sensed for some time that she was out of step with most of her colleagues, who were more conservative and process-driven. But it wasn’t until she had a session with Manhattan career coach Shoya Zichy that she discovered the insight and liberation that comes of learning your personality type.

Cutler, of Syosset, learned her natural inclination was to be more spontaneous and action-oriented, instead of getting bogged down by schedules and hierarchies. That puts her in a personality group that Zichy says makes up 27 percent of the population. For Cutler, the finding was something of an epiphany — that “I’m not crazy.” That newfound awareness led her to leave her job and go on to co-found a boutique accounting firm in Manhattan — where, she says, her enthusiasm is not stifled by “the red tape of the corporate world.”

Such can be the value of looking beyond basic skills and interests and learning about the factors that make us tick — what organizational development consultant and author Travis Bradberry describes as our “tendencies, motivations and preferences.” Most of us “know more about the astrological traits of ourselves and others than we do about our own personalities,” he writes in his new book, “The Personality Code: Unlock the Secret to Understanding Your Boss, Your Colleagues, Your Friends … and Yourself” (Putnam, $24.95).

Increasingly, individuals are learning about personality assessments as they work with the growing number of life coaches who, for a fee, help them get to the root of who they are and set goals accordingly. And as employers continue to emphasize team and collaborative skills, Mary Speed-Perri, a training and organizational development consultant in Northport, says they’re bringing in consultants to administer such assessments — in part to help employees and bosses alike determine their natural work-style preferences.

So what exactly can such assessments reveal? For starters:

The degree to which you’re more naturally energized by being with people or by being alone.

If you’re more comfortable sticking with tried-and-true solutions or brainstorming new ones.

If you work better when your day is predictable or if you’re ignited by a crisis.

When we’re in roles and cultures that allow us to play to our natural strengths and inclinations, we experience more satisfaction and less stress and burnout, says Zichy, author of a new book, “Career Match: Connecting Who You Are with What You’ll Love to Do” (AMA, $15). So tests that help us see our overall preference patterns can allow us to make more informed choices as to jobs and work environments. And we might see, as Cutler did, that we are not the problem — but, rather, that our personality type is underrepresented in our particular workplace.

Such test findings have an added benefit, Speed-Perri says: They help us to see that co-workers and bosses, too, are hard-wired in certain ways. “They’re not trying to irritate me,” she says. “That’s just who they are.”

Marla J. Kreindler , a senior partner with a law firm in Chicago, says, “I like to have 10 people calling me — it’s energizing.” Most of her colleagues do not share that trait, she told an audience recently at a panel event put on in Manhattan by The Financial Women’s Association of New York . Kreindler, though, says she and her firm recognize the value of having different personality types on board. So when a client calls requesting a firm member to be in London on Tuesday, some colleagues may look pained — but Kreindler says her response is “what can be more fun than that?”

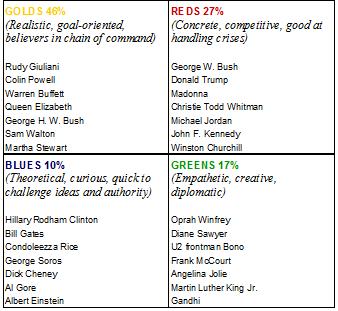

Such preferences make her a “red” in the color coding personality system that’s at the heart of Zichy’s book, which she describes as an introduction to the Myers-Briggs Type Indicator, a personality inventory with 16 major types, based on the work of C.G. Jung. At their most stripped down versions, Zichy’s basic groups look like this:

Reds: Those who are competitive, adventure-oriented, good at improvising and handling crises. Many reds are drawn to entrepreneurship, politics and action-oriented professions, like firefighter and police officer.

Greens: Creative types who tend to be empathetic and diplomatic, and who are also sensitive to criticism. Many greens go into writing, marketing, public relations.

Golds: Those goal-oriented, well-organized people who favor procedures and chains of command, drawn often to administrative, accounting and certain banking roles.

Blues: Those who relish theory, complexity, learning, spotting the big picture, challenging authority. You’ll see blues drawn to professions such as professor, scientist, management consultant.

Freddy Smith , a financial adviser from Wantagh who attended the Financial Women’s Association event, says such personality typing can help him determine which clients are more comfortable with which investment instruments. He says he’s learned that greens tend to invest time in finding a reliable person to whom they can trust their financial matters, while reds prefer more oversight and control.

Certainly, though, no one is saying that people always fit neatly and easily into personality groupings. On the tests, some people may describe themselves as they think they should be, as opposed to how they really are. And, there are numerous possible combinations of styles and preferences. Bradberry, who has done work for Starbucks, as well as the U.S. Department of Homeland Security, outlines 14 fundamental personality types — with as many as 123,000 possible variations. The underpinning of his work is the DISC assessment, which stands for dominance, influence, steadiness, conscientiousness.

“Your personality type doesn’t decide if you’re successful … your awareness of it does,” he says — explaining that just because you’re an introvert doesn’t mean you can’t be a successful salesperson. Bradberry’s book draws on a 10-year research project with 500,000 participants, which found that 82 percent of top performers were highly self-aware. Looked at another way: Just 2 percent of low performers had a good fix on their personality traits.

There are lessons for employers, as well: Judith E. Glaser, an executive coach in Manhattan and author of “The DNA of Leadership: Leverage Your Instincts To: Communicate, Differentiate, Innovate” (Adams, $24.95), warns against excluding workers from teams and projects based on personality type. Teams function best, she says, when there’s diversity.

She also warns against self-labeling: Don’t assume because you’re in one personality category that you don’t also have “hidden strengths” that, when developed, might move you more toward another. That’s been the case with Kathleen Waldron , a former banker who’s president of Baruch Col lege in Manhattan. At the Financial Women’s Association panel , Waldron said she had been a gold — but as she adapts to her role in academia, she sees herself moving more to the blue category.

Here’s how Zichy suggests we look at ourselves when we learn about our personalities: Your brain is a village with four neighborhoods. You’ll have a preferred neighborhood, one where you feel “most productive and energized,” she says. And the others are accessible at any time — albeit, sometimes with a higher level of stress.